"Loving Vincent": The story behind

the world's first fully painted film

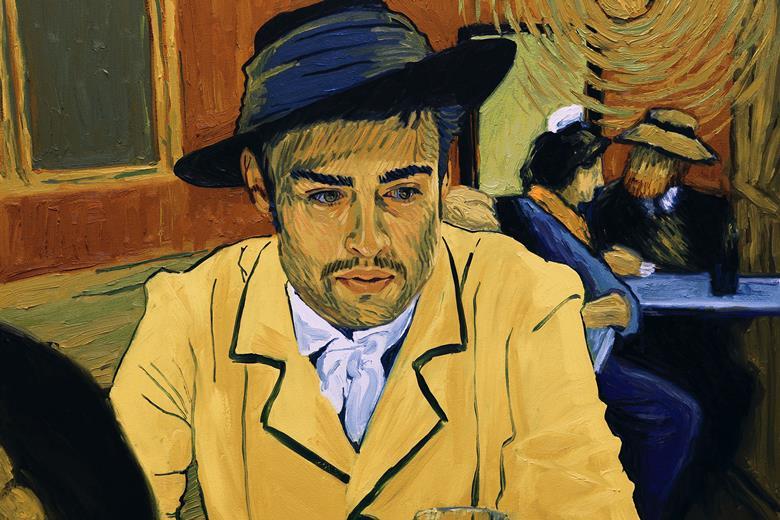

Billed as the world’s “first fully oil-painted animated feature”, Loving Vincent has tapped into the worldwide fascination with the life and work of Vincent van Gogh. First released in the US in September by Good Deed Entertainment, the film has grossed more than $3m in the territory, and has also achieved healthy box-office returns in markets including the UK, Italy and Poland — all $1m-plus success stories.

This idiosyncratic and wildly ambitious project was first conceived around a decade ago by Polish filmmaker Dorota Kobiela, who had trained as an artist before beginning to work in cinema. “While she [Dorota] was doing her research, for inspiration, she was re-reading the letters of van Gogh,” says Kobiela’s co-director and partner, Hugh Welchman. Kobiela had first encountered the letters when she was a student. She looked at them again when she was in her late 20s, precisely the age of van Gogh when he embarked on his painting career, having failed at everything else he had tried.

“Vincent’s letters for me work on many levels,” Kobiela says. On a personal level, she found them “consoling” in her own darker moments: “They are a great source of knowledge, very private, very intimate and very genuine.” Revealing his love of art and literature, the letters showed van Gogh as a far more sympathetic person than the tortured madman portrayed in books and Hollywood biopics such as Vincente Minnelli’s Lust For Life (1956).

In her student days, Kobiela had written a paper about mental health and creativity, which looked at both van Gogh’s work and that of English playwright Sarah Kane, who committed suicide in 1999 aged only 28. Kobiela’s vision for her film was “to use art to tell the story of an artist”.

The Polish Film Institute was an early supporter of the project, which was originally conceived as a short. “But what happens in Poland is that they send you the grant letter six months before they give you the money. That’s when she took a job at my company and that’s when we fell in love,” Welchman recalls of how Kobiela came to work at BreakThru Films, the outfit through which he produced the 2006 Oscar-winning animated short Peter & The Wolf.

Welchman confesses freely that, at first, he did not know much about van Gogh beyond the fact that he “was mad, cut off his ear and did these swirly paintings that sold for lots of money”. Nonetheless, he soon became as obsessed as Kobiela with the visionary Dutch artist. “Because of her, I was reading these books that were lying around the house and I became completely blown away by his story,” he says.

As a producer, Welchman spotted an opportunity. He had seen the crowds queuing for hours outside van Gogh exhibitions. Having worked in animation for many years, he was also intrigued by Kobiela’s visual style. “It’s an oil painting coming to life. It’s a stop-motion technique. What you are seeing is oil painting moving across canvas, which gives you a very kinetic and quite physical feeling,” he explains.

This idiosyncratic and wildly ambitious project was first conceived around a decade ago by Polish filmmaker Dorota Kobiela, who had trained as an artist before beginning to work in cinema. “While she [Dorota] was doing her research, for inspiration, she was re-reading the letters of van Gogh,” says Kobiela’s co-director and partner, Hugh Welchman. Kobiela had first encountered the letters when she was a student. She looked at them again when she was in her late 20s, precisely the age of van Gogh when he embarked on his painting career, having failed at everything else he had tried.

“Vincent’s letters for me work on many levels,” Kobiela says. On a personal level, she found them “consoling” in her own darker moments: “They are a great source of knowledge, very private, very intimate and very genuine.” Revealing his love of art and literature, the letters showed van Gogh as a far more sympathetic person than the tortured madman portrayed in books and Hollywood biopics such as Vincente Minnelli’s Lust For Life (1956).

In her student days, Kobiela had written a paper about mental health and creativity, which looked at both van Gogh’s work and that of English playwright Sarah Kane, who committed suicide in 1999 aged only 28. Kobiela’s vision for her film was “to use art to tell the story of an artist”.

The Polish Film Institute was an early supporter of the project, which was originally conceived as a short. “But what happens in Poland is that they send you the grant letter six months before they give you the money. That’s when she took a job at my company and that’s when we fell in love,” Welchman recalls of how Kobiela came to work at BreakThru Films, the outfit through which he produced the 2006 Oscar-winning animated short Peter & The Wolf.

Welchman confesses freely that, at first, he did not know much about van Gogh beyond the fact that he “was mad, cut off his ear and did these swirly paintings that sold for lots of money”. Nonetheless, he soon became as obsessed as Kobiela with the visionary Dutch artist. “Because of her, I was reading these books that were lying around the house and I became completely blown away by his story,” he says.

As a producer, Welchman spotted an opportunity. He had seen the crowds queuing for hours outside van Gogh exhibitions. Having worked in animation for many years, he was also intrigued by Kobiela’s visual style. “It’s an oil painting coming to life. It’s a stop-motion technique. What you are seeing is oil painting moving across canvas, which gives you a very kinetic and quite physical feeling,” he explains.

Special delivery

Loving Vincent is structured like a detective story. Armand Roulin (voiced by Douglas Booth) is the young man from Arles carrying an unopened letter that van Gogh wrote to his brother shortly before his death. As he tries to deliver the letter, Roulin discovers more and more about the artist.

Kobiela’s original plan was to make the film as an animated documentary. “The trouble was that it was just too static,” Welchman says. They needed “a journey” and a lead character. Armand seemed like the perfect protagonist. He was the son of one of van Gogh’s closest friends, postman Joseph Roulin, the subject of a famous painting. Armand’s initial attitude towards the artist was sceptical and resentful — van Gogh had antagonised his mother. He had little time for the artist but the more he found out, the more he came to admire him.

Loving Vincent was a complicated film to make. The first step was to write a script, provide a storyboard and “do the visualisation” on the computer. Next came the live-action shooting (mostly done at Three Mills Studio in London) with a high-profile cast including Booth, Jerome Flynn and Saoirse Ronan. Then, the oil painting animation began in earnest. There were 125 animators, from 20 different countries, and each was expected to provide a third of a second of material each day. The budget was $5.5m.

The producers created a website in order to recruit new painters. This included a trailer of the work they had done so far. When one of Booth’s fans uploaded the trailer to Facebook, it was watched 2 million times in 24 hours — and 200 million times in all. As news of the project spread online, so media attention grew. “Some of the tough conversations we had been having with financiers got a lot easier,” Welchman remembers.

Ivan Mactaggart of the UK’s Trademark Films (the outfit behind Parade’s End and My Week With Marilyn) had met Welchman through a mutual friend in 2012. He told the filmmaker that Trademark did not “do animation” but when Welchman showed him an early trailer, “I watched that for 90 seconds and at the end, I said, ‘OK, we do do animation!’” Mactaggart’s business partner David Parfitt agreed the film fit the Trademark brand simply on quality grounds.

Trademark helped recruit Edward Noeltner of Cinema Management Group (CMG). The US sales agent had come to the UK at the invitation of Film London and met Parfitt. Noeltner was shown a trailer and, like Mactaggart, was instantly enthralled.

The filmmakers had approached the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam early on. “They were bemused by us at the beginning,” Welchman says. “They liked us and they knew that we were taking it very seriously. They understood we were studying the paintings very rigorously.”

Kobiela and Welchman asked experts at the museum detailed questions about the order in which van Gogh applied paints, and whether he would do under-drawings. “They liked the concept trailer we showed them but I don’t think they grasped the project in its entirety,” he says.

Whatever the initial doubts, the Van Gogh Museum administrators supported the filmmakers and eventually hosted a premiere. Other prominent museums including the National Gallery in London and Musée d’Orsay in Paris have also supported the film. Loving Vincent has now spawned an exhibition of its own in the Netherlands and there are plans to sell off the paintings created for the movie.

Having tackled van Gogh, Kobiela and Welchman are currently plotting an equally ambitious project — a “painted horror film based on the late paintings by Goya”. These are pictures that revealed the cruelty and extreme violence of war.

Kobiela’s original plan was to make the film as an animated documentary. “The trouble was that it was just too static,” Welchman says. They needed “a journey” and a lead character. Armand seemed like the perfect protagonist. He was the son of one of van Gogh’s closest friends, postman Joseph Roulin, the subject of a famous painting. Armand’s initial attitude towards the artist was sceptical and resentful — van Gogh had antagonised his mother. He had little time for the artist but the more he found out, the more he came to admire him.

Loving Vincent was a complicated film to make. The first step was to write a script, provide a storyboard and “do the visualisation” on the computer. Next came the live-action shooting (mostly done at Three Mills Studio in London) with a high-profile cast including Booth, Jerome Flynn and Saoirse Ronan. Then, the oil painting animation began in earnest. There were 125 animators, from 20 different countries, and each was expected to provide a third of a second of material each day. The budget was $5.5m.

The producers created a website in order to recruit new painters. This included a trailer of the work they had done so far. When one of Booth’s fans uploaded the trailer to Facebook, it was watched 2 million times in 24 hours — and 200 million times in all. As news of the project spread online, so media attention grew. “Some of the tough conversations we had been having with financiers got a lot easier,” Welchman remembers.

Ivan Mactaggart of the UK’s Trademark Films (the outfit behind Parade’s End and My Week With Marilyn) had met Welchman through a mutual friend in 2012. He told the filmmaker that Trademark did not “do animation” but when Welchman showed him an early trailer, “I watched that for 90 seconds and at the end, I said, ‘OK, we do do animation!’” Mactaggart’s business partner David Parfitt agreed the film fit the Trademark brand simply on quality grounds.

Trademark helped recruit Edward Noeltner of Cinema Management Group (CMG). The US sales agent had come to the UK at the invitation of Film London and met Parfitt. Noeltner was shown a trailer and, like Mactaggart, was instantly enthralled.

The filmmakers had approached the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam early on. “They were bemused by us at the beginning,” Welchman says. “They liked us and they knew that we were taking it very seriously. They understood we were studying the paintings very rigorously.”

Kobiela and Welchman asked experts at the museum detailed questions about the order in which van Gogh applied paints, and whether he would do under-drawings. “They liked the concept trailer we showed them but I don’t think they grasped the project in its entirety,” he says.

Whatever the initial doubts, the Van Gogh Museum administrators supported the filmmakers and eventually hosted a premiere. Other prominent museums including the National Gallery in London and Musée d’Orsay in Paris have also supported the film. Loving Vincent has now spawned an exhibition of its own in the Netherlands and there are plans to sell off the paintings created for the movie.

Having tackled van Gogh, Kobiela and Welchman are currently plotting an equally ambitious project — a “painted horror film based on the late paintings by Goya”. These are pictures that revealed the cruelty and extreme violence of war.